The Bumpy Ride to Making Crash Helmets Mandatory

Crash helmets might save lives but getting people to wear them was an uphill task.

By Sharad Pandian

These days, everyone on a motorcycle or scooter wears a crash helmet so we don’t give it a second thought. It might come as a surprise then to learn that until about 50 years ago, wearing a helmet while riding in Singapore was completely voluntary. As one might guess, this also meant that the vast majority of people did not bother with wearing any protective headgear at all. It was only in 1971 that the government passed a law that made helmets mandatory.

The run-up to this law saw fierce public debate over the need for such legislation. Opponents of the law marshalled a number of arguments for their cause, ranging from the inconvenience of carrying around a helmet to more abstract concerns about individual liberty. Even after the law’s passing, many did not easily yield to the new order. “I have been happy riding a scooter without a crash helmet for the past 11 years”, wrote a reader to the Singapore Herald in January 1971. But now that the law mandating helmets “was forced on us,” he declared that he would rather get rid of his motorbike rather than wear a helmet.1

The push to have mandatory helmets dates back to the 1950s, when groups in Singapore and Malaya began lobbying for such a law following a heated debate in Britain over this issue. In 1941, British neurosurgeon Hugh Cairns - who dedicated his career to studying head injuries suffered by motorcyclists - convinced the British Army to mandate helmets for its riders. When this policy sharply reduced deaths, Cairns came to the conclusion that the universal adoption of crash helmets would “result in considerable saving of life”.2

After the war, the matter was taken up in the UK Parliament. During the 1956 parliamentary consideration of its Road Traffic Bill, both sides of the house opposed making helmets compulsory, regarding this as unacceptable interference with people’s liberty.3 (It was not until 1973 that Britain finally passed a national law mandating crash helmets.4)

The debate in the UK over helmets inspired groups in Singapore and Malaya. Here, events proceeded alongside British developments, remaining distinct and yet informed by them. In 1957, the Straits Times reported that the English medical journal The Lancet had found that “crash helmets reduced the proportion of deaths and serious head injuries by 40 percent in motorcycle accidents”. “With so many young speed maniacs at large, the crash helmet question could well be considered by the Singapore and Federation governments,” mused the Straits Times.5

In 1960, the Automobile Association of Singapore, the Singapore Motor Club, and prominent army personnel came out in favour of compulsory crash helmets for motorcyclists and their pillion riders. It would be for their own safety if these motorcyclists were compelled to wear crash helmets, argued Milton Tan, president of the Automobile Association, in November 1960.6

Some members of the public agreed. Writing to the Straits Times in March 1962, a reader urged the government to force riders to wear helmets. The reader noted that as wages improved and hire purchase options became increasingly available, more and more motorcycles and scooters would end up on the roads, and more deaths and injuries would result if the riders did not have protective headgear.7

Apart from the personal cost to individuals and families, the high number of traffic accidents in Singapore in the 1950s and 1960s exacted an economic cost on the young nation as productive workers died or became severely injured. According to a United Nations safety expert, road accidents alone cost Singapore $130 million in 1970.8 “[T]he loss or damage to a productive life is not a mere loss to the individual involved but a loss of a factor of production to the nation,” noted a reader of the Eastern Sun in 1969.9

Crash Helmet Woes

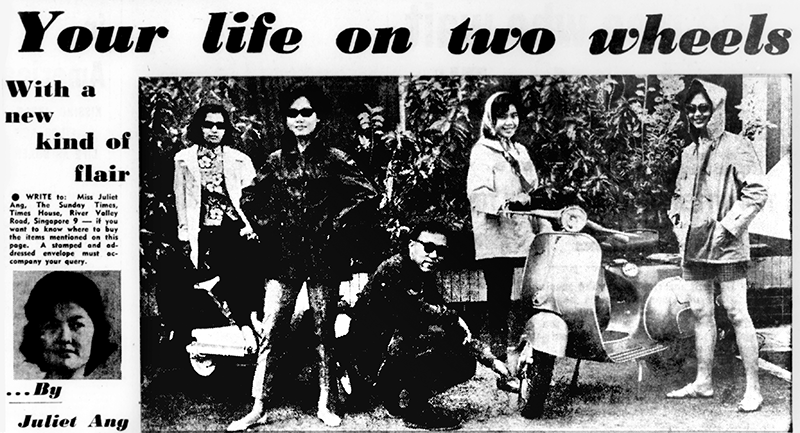

However, as in the case of Britain, not everyone here was in favour of the idea. The Vespa Scooter Club in Kuala Lumpur, for example, opposed wearing helmets in town and wanted to confine helmets to the highways where people tended to speed. Club president Jimmy Koh told the Straits Times in December 1963 that “scooterists have to ride slowly in town because of the heavy traffic. Our members, therefore, feel that compulsory wearing of crash helmets is unnecessary”. “Furthermore,” he added, “we are against having to wear helmets for riding in town because every time we take them off, we have to comb our hair.”10

There was also the hassle of having to deal with a helmet when not riding. “Think of the inconvenience it will cause if you have to carry that extra burden when you go for a show, when you go on a date, or wherever you go,” wrote a reader to the Straits Times in January 1964. “I am sure all scooter riders are old enough to look after themselves. Must somebody tell them how to look after their own heads?” she wondered.11

Leaving the helmet with the motorcycle or scooter was not an option, said another. “Whereas a motorist can leave his safety belt in his locked car we cannot leave our crash helmets on our machines and expect to find them still there when we return.”12

One rider argued that he had been travelling to and from work daily with his wife on a motorcycle for the past eight years without any mishap. His wife refused to wear a crash helmet, so he pleaded with the government to understand “how awful and inconvenient it is for the pillion rider to wear a crash helmet”. He added in jest: “Otherwise, I have to give up my bike - or my wife.”13

Finally, there was the argument for individual autonomy. “Scooter girl” argued that riders should be allowed to make up their own minds about the risks involved and whether to bear them, since “though I am by no means enthusiastically looking forward to breaking my neck it still is my neck - and the choice must be left to me”. 14

Making Crash Helmets Mandatory

Given the extent of the opposition to making helmets mandatory in Singapore, credit must be given to the man who ceaselessly campaigned for it - Milton Tan, the president of the Automobile Association of Singapore. For Tan, wearing a helmet “was not a blow at individual liberty”. Rather, “It is the minimum discipline we must accept if we want to have a highly motorised society and stay alive”. He began advocating for making helmets compulsory for motorcyclists and their pillion riders as early as 1960.15

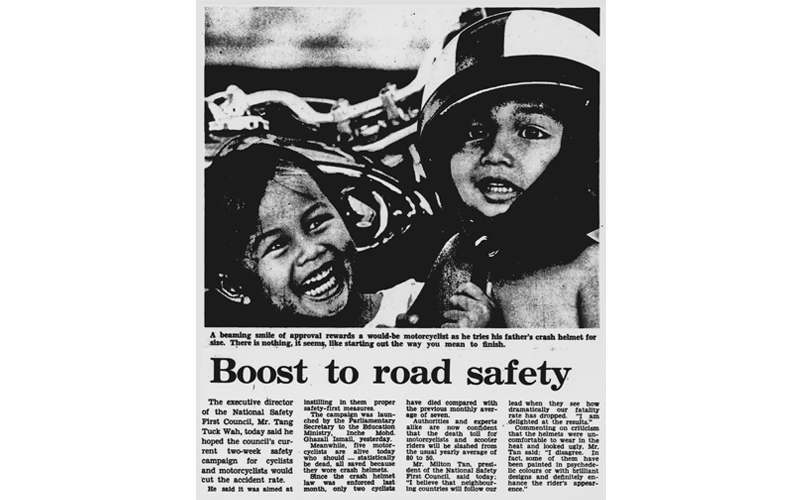

Subsequently, when the National Safety First Council of Singapore (NSFC) was formed in 1966 to coordinate road safety efforts, Tan was elected its first chairman.16 He carried on his campaign to make helmets mandatory, using the council as a platform. In May 1968, the council worked with the government to roll out a three-week-long awareness campaign with the slogan, “A crash helmet can save your life”. The campaign - publicised through television, radio, newspapers, Rediffusion, posters, pamphlets and banners - included an exhibition, a poster competition and a motorcycle procession.17

Tan’s education campaign had critics, even among those who backed the idea. People complained that as it was not backed by legislation, it did not have teeth. “A great number of drivers of all kinds in Singapore are fiends who are converting its roads into devils’ highways and you won’t stop them with colourful floats and gentle persuasion,” wrote K.E. Hilborne to the Straits Times in March 1968. “They will only respond to two things: money and force - in a word legislation.”18

Another letter writer, D.G. Ironside, agreed with Hilborne, highlighting the fact that if airlines did not require their passengers to fasten their seat belts, not all would comply. “Legislation must come,” he wrote, “Why not now? If Mr Milton Tan and his colleagues are not prepared to press for such legislation, how do they justify such an attitude?”19

In response to Ironside, Tan explained that the NSFC was not against legislation. “[W]e do not believe that legislation is the complete substitute for publicity and education. Whether or not there is legislation there must be publicity and education,” he argued. “We, in the National Safety First Council, are naturally fully in support of such a campaign. But such support is in line with, and not contradictory to, consideration of legislation should the need be established.”20

Indeed, before the end of that year, Tan would ask the government to introduce legislation to mandate helmets for motorcyclists and scooterists. His argument was that even after the campaign, out of the country’s 100,000 motorcyclists and scooterists, only 25 per cent wore helmets. “The remaining 75 per cent must be made to wear helmets by legislation,” he said.21

In August 1968, the Singapore government set up the Traffic Advisory Board to carry out “a comprehensive review of all relevant legislation pertaining to road transport”.22 (Tan had spearheaded the formation of this board: he had both called the initial meeting to discuss its formation in 1965 and served as the chairman of the pro tem committee which sought its formation.23) Not only was he a member of this board, Tan had also been specifically advised by the government to broach the issue of crash helmets to it.24

Unsurprisingly, the board recommended making crash helmets mandatory in its interim report and Communications Minister Yong Nyuk Lin informed Parliament that the government accepted the recommendation.25

The crash helmet was made mandatory for “L” licence holders in February 1970 and for all motorcyclists and scooterists, including pillion riders, in Singapore in January 1971 through an amendment to the Road Traffic Ordinance.26 This meant that Singapore ended up mandating helmets more than two years before Britain got around to it.

To ensure that the helmets were of adequate quality, Singapore adopted the existing British Standard’s specifications for helmets, with the Singapore Institute for Standards and Industrial Research (SISIR) appointed the testing agency for all helmets.27

Circumventing the New Law

Of course, the passage of the law did not immediately settle the problem. In the first month of the law taking effect, 220 people were booked by the police for riding without a helmet - and this figure only included those who were caught. What was also not recorded was the number of riders who had given up their vehicles in favour of alternative modes of transport, as some motorcyclists said they would do.28

Motorcycle sales fell, indicating that the new law did not simply convince riders to wear a helmet but also changed their usage patterns. “Motorcyclists themselves feel that with parking space restricted and the traffic police becoming increasingly strict with owners of machines parked on sidewalks, most now prefer to leave them at home and come to work by bus or pirate taxi,” reported the Singapore Herald in July 1970.29

There was also the question of exemptions and boundaries. In 1970, the Singapore police announced that Sikh motorcyclists would be exempted from the law on religious grounds. As Peshora Singh, a doorman at an Orchard Road restaurant, explained to the Singapore Herald, “it’s hardly possible for me to put on a crash helmet unless I take off my turban and have a hair-cut - but that’s against my religion”. A police spokesperson explained their decision to grant the exemption: “We have to respect all religious beliefs in this multi-racial society.”30

Sikhs in Malaysia also sought an exemption from this law, and then even exemptions needed clarification. In 1977, a Sikh woman in Ipoh wore a piece of cloth tied around her head and neck instead of a helmet when riding pillion on a motorcycle. She was charged with flouting the crash helmet law, but when the case went to court, the defence counsel argued that since there was no definition of “turban” in the rules, the court could not rule she was not wearing one. The judge dismissed this line of reasoning, deciding instead that the material she was wearing was more akin to a scarf than a turban. The woman was eventually found guilty and fined $50.31

As the law pressured riders into wearing crash helmets, they came up with ingenious ways to overcome the inconvenience of having to lug them around. One popular practice was to drill a hole in the helmet so that it could be chained to the motorcycle. Although there was no law against wearing helmets with holes drilled through them, safety experts warned against such an act. “[A] hole drilled in a helmet would weaken the shell, and many people drill holes in the crowns of their helmets. The crown is the part which would take the most strain in a head-on crash,” cautioned Winston Lee, secretary of the Singapore Grand Prix and vice-president of the Singapore Motor Sports Club.32

Another common practice was for riders to wear helmets that were slightly larger than their heads, which kept them cool in Singapore’s warm climate but offered less protection as the loose fit increased the risk of the helmets falling off.33

Then there was the trend of so-called “made-to-measure” crash helmets, which were illegal knock-offs of more expensive brands. A “made-to-measure” helmet would cost about $45, compared to those tested and approved by SISIR, which sold for between $90 and $130.34

The Use and Misuse of Crash Helmets

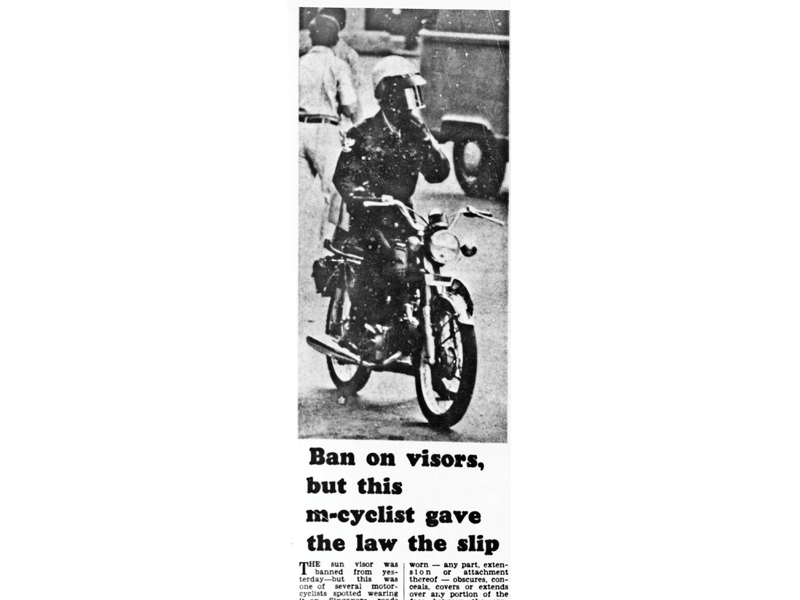

Very quickly, helmets went from saving lives to also threatening them. In December 1979, a man died from a fractured skull and bleeding in the brain after being beaten by a gang using crash helmets.35 A spate of robberies committed by people wearing visored helmets between 1974 and 1975 led to the governments of both Singapore and Malaysia banning full-face helmets and those with visors from April 1975 as these concealed the identities of the wearers.36

The ban in Singapore stirred up much debate in the press. In February 1975, a group of 30 motorcyclists appealed to the government to reconsider its ban on helmets with visors. They pointed out that the robbers had been wearing inexpensive full-face helmets not approved by SISIR, and so the government could simply stop the supply of these cheaper helmets. They also suggested banning motorcyclists from wearing helmets when not riding and banning only dark visors. After all, they argued, even without helmets, robbers would simply disguise themselves with sunglasses.37

“Singapore takes one pace backwards on road safety,” bemoaned Jim Watkins, motoring editor of the New Nation. “It seems ironic, after a month-long safety campaign which succeeded in reducing casualties on the roads, that law and order should be cited as a reason for abandoning the pursuit of maximum safety.” He argued that riding without protecting one’s eyes was “stupidity of the first order” since insects, gravel fragments or grit from lorries could easily cause a loss of control and subsequently accidents.38

Lee Chiu San, a reporter with the New Nation suggested that owners be made to display their vehicle number prominently on their helmets, stripping the wearer of anonymity, while Sam Brownfield, secretary of the Singapore Motor Sports Club, proposed banning tinted visors instead of completely doing away with visors.39

Letters to the press that called for lifting the ban on clear visors continued throughout the 1970s.40 Finally, in November 1980, the Communications Ministry asked the Traffic Police to study the possibility of partially lifting the ban on the use of crash helmets with clear visors. On 1 April 1981, the ban on clear visors was lifted although tinted visors and helmets with chin guards that obscured faces were still not allowed. It was only in April 1993 that the ban on full-face helmets was finally lifted, although the government continued to insist that only SISIR-approved helmets would be allowed.41

If you look up the Road Traffic Act today, you will encounter long blocks of legalese with definitions and clarifications, all of which might give the impression of an abstract bureaucratic artefact. A closer look with a historical lens, however, reveals how the law itself was made, moulded, and adapted by a range of actors in distinct and creative ways. Today, it might seem obvious that riders of motorcycles and scooters ought to wear a helmet, but dig a little deeper, and we find a much more complex and fascinating story.

Notes

Link nội dung: https://pmil.edu.vn/those-who-are-riding-a-motorbike-are-not-allowed-to-take-off-their-helmet-a58487.html